Hi, this is the 6th (and most stupidly named) article of Fifth Industrial, a blog scouting emerging biotechnologies with potential to address biodiversity loss, climate change, animal abuse, and other maladies of the modern economy. See the landscapes on cellular agriculture, mycelium materials, synthetic silk, microbiomics, and deep space food systems.

Why cheese sucks

We all know cheese is a big deal. It’s culinary bedrock in the many societies and integral to the world’s favorite food: pizza. Cheese is roughly a $100 billion market, more than humanity spends on socks (~$40bn), toothpaste (~$20bn), ketchup (~$20bn), jerky (~$4bn), and aspirin (~$2bn) combined.

Cheese is one of those everyday things that people have strong opinions about, like toilet paper roll configuration, bacon, sports legends, or thermostat settings. My opinion: cheese sucks. Sure, a lot of it tastes delicious. But, cheese unequivocally sucks for the planet and animals, and arguably sucks for human health.

Voluntary beef reduction is hugely popular among Westerners who now seek to cut back for personal health, environmental, and to a tiny extent animal welfare reasons. Condé Nast’s culinary magazine, Epicurious, announced in April 2021 that it would stop publishing beef-related content for sustainability reasons. Most, however, are less eager to give up cheese. It’s a hard truth, but animal meat and animal dairy are the same industry, which motivates this article on alternative forms of cheese and methods of cheese production. Why:

Animals: To induce lactation, cows(etc) are impregnated, mostly forcefully. Most female offspring become dairy cows while typically male offspring are sold to be slaughtered for veal. At the end of a dairy cow’s lifecycle — or before, when “market forces” dictate it — they are slaughtered too and put into the meat supply chain. Historically, the coagulant used for curdling cheese was sourced from the stomaches of slaughtered calves (more on this later). Cheese, like meat, equals slaughter.

Environment: Cheese is the #1 most GHG emitting non-meat food source per kg, only behind cow meat, sheep meat, and farmed shrimp. Cheese is the #1 most water-intensive food. The industries prop each other up and engage in systematic campaigns against climate science to avoid reform, particularly after a prominent UN FAO report in 2013 found that 14.5% of all GHG emissions comes from the livestock sector.

Animal-based cheese, essentially concentrated milk, contributes 55x more emissions than nuts, per kg. Source: Our World in Data, updated June 2021. Health: Like meat, cheese is a major dietary source of saturated fats which are attributable to cardiovascular disease and associated with hormone imbalances, acne, asthma, some cancers, and hypertension. That’s not to mention the public health risks of zoonotic disease (like mad cow) and widespread antibiotic use (which isn’t supposed to happen in the US but does) in dairy. Plus, cheese is physiologically addictive due to opioid-like compounds.

Why then, can we not give up cheese? Because the alternatives that are widely available now suck too. They’re largely better for animals, the environment, and pandemic prevention, but often are high in saturated fats, starches, and synthetic additives (though I don’t intended to appeal to the naturalistic fallacy here). More importantly, most vegan cheeses taste worse, cost more, aren’t available, and don’t deliver on important functionality like melting.

Luckily, there are at least 130 companies working on technology to create vegan cheeses that can compete with conventional versions. I’m optimistic that we can have cheese that is delicious, nutritious, industrial, artisanal, humane, affordable, safe, and sustainable.

In this post, I’ll analyze the new biotechnologies underpinning the vegan cheese of the future.

What’s in here?

My soapbox: you just finished it

What cheese is: history & process

The future of cheesemaking tech: landscape; top players and technologies, categorized by approach- conventional food science, vegan artisanal, industrial cultured, precision-fermentation, microbial biomass, plant molecular farming, and animal cell culture

What cheese is: become a cheese whiz in 30 seconds

Definition and basic science

The use of dairy standards of identity like “milk”, “cheese”, and “butter” has been a battleground in the US and Europe. I’ll skip over this imagined crisis predictably resulting from the desperation of a threatened industry and posit this:

Cheese-making is an ancient biotechnology devised to concentrate, flavor, and store milk. Cheese’s linguistic origins are “to ferment, make sour”. Cheese is semi-solid coagulated milk (“curd”), traditionally colonized by microbes that bolster nutrition and flavor. Animal-based curd is made of mostly globular casein proteins, but other molecules like lipids matter too.

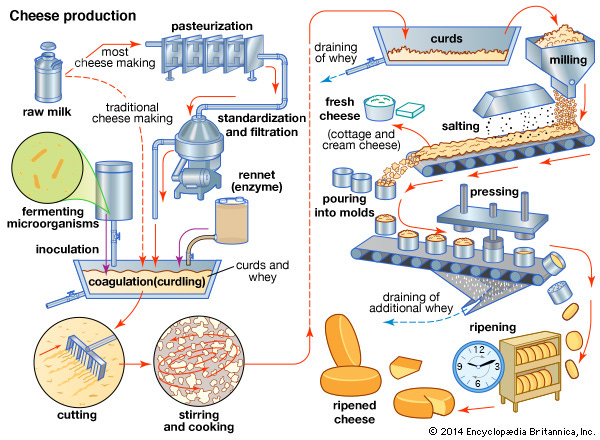

The essence of cheese production is

Coagulation of proteins. In bovine milk, up to 90% of the proteins are classified as caseins which curdle beautifully thanks for colloidal chemistry. It doesn’t have to come from a mammary gland to coagulate like cow milk. Tofu is just soy curd. In cheese, coagulation is induced by chymosin or pepsin — key enzymes in rennet, historically sourced from slaughtered animal stomaches but now 80-90% of chymosin is produced via microbial fermentation. Clara Foods just launched the first fermentation-derived pepsin.

Removing moisture and whey. Whey protein is a byproduct used to make “whey cheese” like ricotta. Add salt too.

Fermentation and/or aging. The magic of cheese’s flavor and pungency has long been in the microbial communities of yeast and bacteria that colonize it. Commodity cheese has given way to the same sterile, chemo-mechanical food science that gave the world cheap, tasty food like PopTarts. The best vegan cheeses so far are focused on bringing this modern alchemy back.

History

Historians theorize cheese was “invented” in 8,000 BC when sheep milk was stored in a dead sheep stomach, where the rennet enzymes and natural microbes caused the milk to curdle and ripen.

Ruminants like cows historically would eat grasses and convert them to milk (and flesh) with the help of cellulose-digesting bacteria living in their stomaches. Nearly all animal cheese consumed comes from ruminants: cows, sheep, goats, water buffalo, reindeer, yaks, and camels in particular. There is no giraffe cheese yet as far as I can tell. Non-ruminants animals like pigs or cats could also be milked, but aren’t in practice.

Plant-milks have also been around for hundreds of years. Almond milk was popular in Medieval Europe and soy milk became popular in China in the 14th Century. The first vegan “cheeses” were made of fermented soy in 16th Century China.

In recent decades in the US, animal milk hasn’t done well, but cheese has. While U.S per capita liquid animal milk sales dropped 40% from 1975 to 2018, cheese sales rose 269%. Nonetheless, the industrialized cow-milking industry is failing. Some 73% of revenue for the U.S. dairy industry is attributable to government subsidies. In 2019, the largest US dairy company, Dean Foods, filed for a chapter 11 “reorganization” bankruptcy and has been followed by others.

The emerging landscape of alt cheese

Below are some some fast facts on the players and approaches in today’s vegan cheese, alternative cheese, animal-free cheese, CheeseTech, or DeepCheese — whatever you’d prefer to call the category.

Landscape snapshot

According to the GFI company database, there are 133 companies working on making alt cheese. This number is likely much higher due to the number of kitchen-scale brands or purely corporate initiatives not yet tracked in that database. Highlights:

HQ Locations: Europe (65), US/Canada (40), LATAM (9); Asia ex Israel (8); Israel (3). This makes sense, roughly following where most cheese is consumed, except for India which is lagging (on the company-building front, not paneer-consuming front).

Maturity: 2015 is the median founding year of an alt cheese company.

Sales: Per GFI, plant-based cheese grew 42% in 2020 to $270MM in dollar sales in U.S. retail. Top selling US brands include Follow Your Heat, Chao, Violife, Daiya, Miyokos, and Kite Hill — a mix of old-school vegan brands, startups, and big corporate subsidiaries.

Funding: I estimate ~$1 billion in venture capital has been invested in alt cheese startups (does not include buyouts). About 2/3 of that funding has gone to precision fermentation companies, defined below.

Technical approaches to alt cheese making

Most of the companies I’m aware of are taking one of the following approaches:

Conventional Food Science - Processed cheese

In post-WWII America, processed cheese — that which is mixed with emulsifiers, stabilizers, colorants, and flavors — has been extremely popular due to its meltiness and low cost.

The majority of vegan cheeses on the market unfortunately use this approach. They generally don’t taste great, function well, or provide nutritional value. Take Daiya, a company founded in 2008 whose cheese is synonymous with sad vegan pizza, which has ~20 ingredients.

If you look at the ingredient list of Daiya, Boursin Dairy-free, Field Roast’s Chao, Follow Your Heart, etc. you’ll see a theme:

Oil: Particularly coconut, palm, and canola that are high in saturated fat

Starches: Corn, potato, pea, or otherwise it provides binding, filler and of course carbs.

Gels and Gums: Carrageenan, xanthan gum, konjac, cellulose gel, etc. — not necessarily bad, but scary to consumers and certainly worse than a whole food.

Colors and Flavors: there is a huge industry built around just this

I’m not giving up on this approach, as it’s foundational to the food industry. New mechanical processes, enzymatic treatments, and plant ingredients can help deliver improvements on nutrition, taste, and consumer appeal.

Vegan artisanal - the microbreweries of cheese

The next wave of vegan cheese looks more like traditional cheesemaking, just swapping out dairy milk with a plant-based milk. Nut milks have been dominant, particularly cashew and almond, but passionate culinarians have been combining all kinds of plant milks/creams with microbes to culture artisanal cheeses. Like traditional cheesemaking, this approach isn’t alway built-for-scale and so most brands — albeit with delicious products — are still small by design or intent. Examples include SriMu, Core and Rind, and Sayve VEGRAN Natur but there are likely hundreds.

Industrial cultured - vegan cheese 2.0 / traditional fermentation

The cutting-edge plant-based cheeses you can buy all utilize traditional fermentation of cashew, almond, or oat creams (or, rather, emulsions when oils are added) in large stainless steel tanks. This is like how artisanal cheese is made, with microbes added either to the cream itself (like beer brewing) or the “puck” of solid pressed curd (like sauerkraut fermenting). The lactic acid bacteria and yeasts do the heavy lifting, bioconverting the carbohydrates into flavorful and/or nutritious biomass and excretions.

The ten or so leading companies utilizing this approach include Miyokos (California), Kite Hill (California), Treeline (New York), and New Roots (Zurich). Not all are perfectly clean label, containing a few oils, starches, and preservative, but seem to be getting better.

The potential here is massive, and the competitive landscape is heating up. Traditional cheesemakers perfected their craft for hundreds of years, combining milks, microbes, and process conditions using rudimentary methods. Now, computer science, genomics, global plant supply chains, and modern fermentation methods are allowing for high throughput testing of novel inputs, cultures, and bioprocesses in infinite combinations. Learn more at the 2020 GFI State of the Industry Report on Fermentation.

Precision fermentation-enabled - big money moonshot

As mentioned, this is where the VC money has been. Biotech, foodtech, and sustainability folks alike love the story of making real cheese without animals by producing real animal proteins or lipids in microbes in a bioreactor. Most companies — which are largely based in California, Boston, or Berlin — are making casein protein, whey protein, or dairy triglycerides. Leaders include New Culture, Formo, Motif. Perfect Day and it’s $360MM raised will eventually launch cheese with their casein, but have focused on ice cream. There are ~20 companies in this space already — all startups — and nothing is on the market anywhere. Big brand Lisanatti “cheats” on their “plant-based” almond cheese by adding casein purified from cow milk, but it does show that casein as an additive works.

Plant molecular farming

Growing plants is much cheaper than using bioreactors required for precision fermentation, so innovators have deployed another tool from pharma. In essence, through an especially thorny genetic engineering process, you can sometimes get plants to grow the functional animal biomolecules. There are perhaps three companies in this space, all targeting creating casein or whey in soybeans or oat, as far as I know. Nobell (California) just came out of stealth mode with a $75MM Series B from Andreessen Horowitz, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and RDJ’s FootPrint Coalition. Moolec in Argentina and Mozza in California are making headway as well.

Animal cell cultured milk

Yet another way to source real animal proteins and lipids without slaughtering animals is through animal cell culture (think: cell-based meat). Of the tiny group of companies who are culturing mammary gland cells in bioreactors that secrete milk compounds, most are focused on infant formula in the short term. However, milk and cheese are on the table — and theoretically from any animal that can be selected for deliciousness or nutrition. Chinchilla milk anyone? The main benefit here is that the other approaches are a bit reductionist. Milk and cheese are more more than just casein and fat — there are hundreds of compounds at play that are produced by mammary glands. Companies are all early stage and include Biomilq (North Carolina), TurtleTree (Singapore), and Biomilk (Israel).

Microbial biomass

Cheese doesn’t have to be from animal or plant proteins, as a few startups are showing. Nature’s Fynd (Chicago) has raised >$500MM from SoftBank, Blackstone, ADM, Danone et al to solid-state-ferment an extremophile fungi from Yellowstone National Park as a protein source. Among other products, they’re launching a cream cheese analog. Superbrewed Foods takes a similar approach, but using anaerobic fermentation tanks like in biofuels. The potential for radical efficiency and creativity is exciting here, but it’s early innings.