Strange Sympathies: A conceptual ecological recipe for empathy

A dash each of microbiomics, holobiontism, horizontal gene transfer, homology, sentience, biomimicry, involution, and biophilia.

Hi, this is the 9th edition of Fifth Industrial, a blog scouting emerging environmental biotechnologies. See the landscapes on plant cell culture, cellular agriculture, mycelium materials, synthetic silk, microbiomics, deep space food, alt cheese, and alt protein CPG. This edition is a departure from the admittedly technocentric worldview of the publication. It is about biophilia, the love of living things, and kinship with the natural world.

Ecology is not a field of clean cuts; the more we learn about biology, the more jagged and interesting the lines between individual organisms and communities of species, and between species, becomes. A popular appreciation of these craggy boundaries — of the “tangled tree of relation” — could be a boon in environmental and animal advocacy.

This goes well beyond the charismatic symbioses brilliantly illuminated by David Attenborough (like Capybara rodents and fly-eating birds that ride on their backs or ants farming fungus and ranching aphids). By existing, all people are themselves engaged in innumerable, direct, and ancient symbioses.

This article serves to highlight a few of these ways in which humans are interconnected with non-humans: microbiomics, holobiontism, horizontal gene transfer, homology, sentience, biomimicry, involution, and biophilia. Each is briefly described below.

There are no rules for living on this planet, only consequences. What is needed is an open exchange in which sentience shapes the eye and results in ever-deepening empathy. Beauty and blood and what Ralph Waldo Emerson called “strange sympathies” with otherness would circulate freely in us, and the songs of the bearded seal’s ululating mating call, the crack and groan of ancient ice, the Arctic tern’s cry, and the robin’s evensong would inhabit our vocal chords.

-Excerpted from Gretel Ehrlich, “Rotten Ice,” Harper’s Magazine (April 2015), p. 41-50. Emphasis added.

Here are some of the scientific mechanisms which create delightful interspecies fuzziness that enriches humanity’s understanding of Nature:

Microbiomics

A microbiome is a group of microorganisms that are specialized to live in a place. It’s also a place that’s specialized to host the microbes. A classic example: human intestines are as long as 5 meters and with the surface area the size of a studio apartment. That real estate houses literally trillions of symbiotic bacteria and fungi, which not only help digest food, but are linked to proper functioning of the brain, skin, heart, genitalia, and basically everything else. We have an oral microbiome nearly as complex and just as mysterious. Our skin alone hosts a thousand bacterial species. Right now, it’s likely that your body has more microbial cells than human cells — a bit over 30 trillion each. Humans are not unique; we know of complex microbiomes in farm soils, in the forest rhizosphere, hospital walls, probably your refrigerator and certainly in your wine.

The extent of our relationship with these microbiomes is not well understood. It is clear, however, that the relationship is one of reciprocity; they are not under our conscious control and more than we are their locomotive meat puppets. See 5IR Edition #2 for more on microbiomics. It’s microbiomes all the way down.

Holobiontism

A holobiont is a symbiotic consortium of multiple species whose lives are so intimately, inextricably intertwined that are arguably a single biological or ecological unit. This is not just little fishes cleaning big fish’s teeth.

Consider the lichen — those wispy, crusty, plant-ish organisms that cover rocks, trees, and just about anywhere you examine closely. Lichens, of which 3600 types are identified in North America alone, provide food and materials for many animals (including humans) as well as play a key role in soil formation and mineral cycles. They are a phylogenetic chimera consisting of several species, including a fungal host-home, photosynthetic algae, and community of bacteria. Other characterized examples of holobionts include coral reefs (marine invertebrates and algae) and perhaps vibrant frogs and neurotoxin-producing bacteria.

It’s a nice way of conceptualizing an ecosystem and a species in one. Arguably, virtually any organism could be considered a holobiont, as all organisms interact with others in integral ways, whether it be host-microbiome or decomposer-decomposed. The classic "Gaia hypothesis” (also posited by legendary champion of holobiont and endosymbiotic theories, Lynn Margulis) takes this a step further, classifying the Earth itself as a single superorganism. I like this more as a metaphor, at least more than “Spaceship Earth”, which positions life on Earth an engineering challenge to be solved.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT)

Ancestral DNA is not the only source of genetic material for organisms. Endosymbiotic theory posits that eukaryotes (multi-cellular organisms like us) arose when primordial prokaryotes (single cell microbes) consumed other microbes which were assimilated as organelles — mitochondria and chloroplasts (in a process called symbiogensis). This phenomenon doesn’t stop at organelles; there is a burgeoning field of study uncovering how genes move between “unrelated” organisms.

One such area is the lateral movement of genetic material between organisms of different species, called horizontal gene transfer (HGT). It is common in prokaryotes but has been identified in numerous animals. Some researchers predict that hundreds or more of human genes have origins in our microbiome or from parasites through complex processes tied to proximity and infection.

The fact that the human genome is probably not entirely “human” evokes the concept of a metagenome, the collection of all genes in an environmental sample, some unique and some shared. A metagenome isn’t the result of an individual, family, or species, but of a community, without which it would not be possible for nearly any organism to develop a niche or even survive among purely abiotic factors.

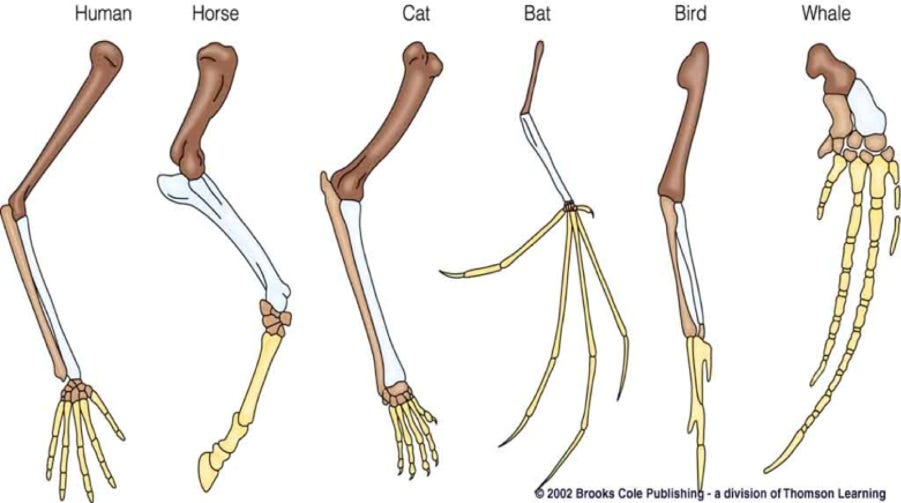

Homology

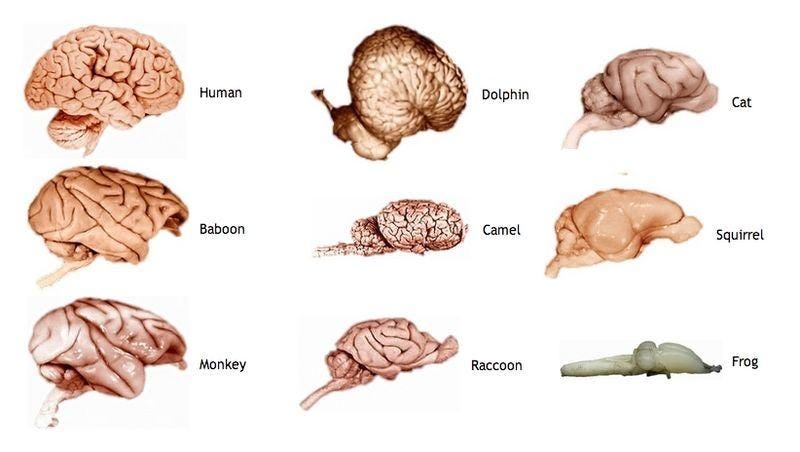

One key implication of evolution is that organisms are not necessarily rationally “designed” but rather are hacked together in situ from existing genes like those that encode for eyeballs, neurons, hair follicles, pointy teeth, flat teeth, etc. This is a result of our shared phylogenetic history through the process of divergent evolution after our common ancestors emerged from the water. Every part of our bodies are the result of happy accidents (helpful mutations) that occurred in other species, and therefore we share many latent anatomical features like “hands” across the animal kingdom. These features (I’ll call morphologs) can be vestigial, like individual finger bones in a whale’s fin or tails in human embryos, or essential like skin and brains.

We share upwards of 60% of our genes with chickens, fruit flies, and even bananas (not to mention nearly identical basic elemental composition). Insects have many of the same organs we do. Human and animal brains share the same general architecture and purpose.

When we understand and appreciate our “inner fish”, it’s not so crazy to imagine the ways in which our minds — intelligence and experiences — are similar to animals. We are made of the same stuff, separated by time and happenstance only.

Sentience

Sentience is that fundamental spark that drives — wills — animals to live, to avoid suffering, to eat delicious foods, and sometimes perhaps to love. Neuroscientific consensus is that consciousness is no less unique to humans than intelligence is or having brains (the substrate of consciousness) is. Rats dream. Chickens can count. Insects can learn. The tiny Zebrafish displays empathy, both sensing a fear response in other Zebrafish and having a response themselves. Almost any animal we look at hard enough provides evidence of ability to feel and think, to have subjective experience, to be a self. Animals can even form complex cultures that mirror our own. Elephants have respected elders. Orcas live in clans. Seals mourn their dead. In a mysterious and often cold universe, a shared state of sentience and culture may be the closest of possible bonds between beings.

Biomimicry

Our understanding of intelligence has moved on from “computing power” (IQ) as a monolith to a theory of multiple intelligences that recognizes additional forms such as emotional, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, and spatial-visual. These, intelligences, and others, are exhibited across many animals; and often put human abilities to shame. The Monarch Butterfly navigates itself between Canada and Mexico and the Arctic Tern flies 25,000 miles a year, while I can’t get to the next town without a GPS. The Five-Ranked Bog Moss (S. quinquefarium) has figured out how to survive as a species for over 300 million years — a thousand times longer than Homo neanderthalensis lasted. Ants have been farming for about 50 million years longer than us.

Now, nature-based design (biomimicry) is a major design movement where we look to bird wings, shark skins, bacterial biofilms, tree trunks for elegant solutions to difficult engineering and social problems. A modern (re)understanding of the power and elegance of nature is already permeating industry, such as with replacement of chemical fertilizers with microbe-based biologicals. We scour nature to discover (not invent) pharmaceutical compounds like penicillin and then produce them with biological machinery like enzymes.

“There is no better designer than Nature.” -Alexander McQueen.

Involution

No man is an island, nor is humanity. Our society would not exist but for the essential roles animals, plants, fungi, and microbes — and not just as resources, but as partners.

Some researchers argue that alcohol played a fundamental role in the formation of human society by motivating the creation of agricultural settlements. Alcohols, plus fermented foods like bread, cheese, kimchi, tempeh, vinegar, ogi, miso — foundational to global cuisine — are the result of co-creation with yeasts and bacteria. In The Botany of Desire, Michael Pollan muses at length whether crops like corn (Z. mays), which humans have cultivated globally now, have instead domesticated us to propagate them; though this does gloss over the terrible conditions inflicted on organisms living in industrial monocultures and factory farms.

For millennia, bacteria, lichens, and mosses have been thanklessly turning inorganic rock into the teeming soil that supports most terrestrial life; yet more evidence of how the dance of life is never a solo act.

These examples are perhaps intuitive, but inform an interesting new perspective in ecology called “involution”. Involution is a theory of affective ecology which puts the lens on the the interdependence and co-evolution of species, rather than their competitiveness in a fictional zero-sum game. For example, whether and how trees of different species in a forest may share nutrients through a mycorrhizal “wood wide web” is an intellectual breakthrough (and frontline of debate) for ecologists.

Biophilia

Biophilia is a term popularized by biologist E.O. Wilson to describe the innate human affection for nature and living things. Such love is as vital as romantic love so a healthy society. This affection is apparent in our culture, from religious myths — like animal deities or devourer-savior cetaceans — to symbolic language — like “holy cow” or “horse around”. What would life be without doting dogs and curious cats, without blossoms in the Spring, without golden autumnal oaks, without the taste of berries at a Summer picnic surrounded by ants, without birdsong or the bouquet of topsoil? Why then, is this not apparent in our everyday actions and priorities? Such are questions for the ecopsychologists, but much is certainly lost in an increasingly urbanizing, digitalizing, and financializing culture with an ever-changing baseline of human dominion.

Conclusion

These concepts - microbiomics, holobiontism, horizontal gene transfer, homology, sentience, biomimicry, involution, and biophilia - paint a picture of a Nature that is deeply intertwined among itself and with humanity. As we sterilize our bodies, our fields, our forests, our soundscapes, our empathy, and our humility, we die little deaths in the tangle.

We need social change. Otherwise, addressing humanity’s problems like food insecurity will likely not be possible, even despite a global surplus of food production capability. This article hopes to serve as a scrap of a recipe for a contagion of empathy, awe, or appreciation.

The Gaianists, back-to-the-landers, and others of the “New Age” movement made a compelling attempt to reform society but failed to achieve durable mainstream appeal. Belief in a global superorganism, or in the virtue of an agrarian life both demand too much and downplay the role of science.

The fix is perhaps technological in a sense; these insights into biology, engineering, and ecology give us powerful tools to achieve more with less. Perhaps, however, the technology that we most need is an update to our culture: strange sympathies stoked by an appreciation of our togetherness with Nature.

Each

man's[ecological] death diminishes me,

for I am involved inmankind[living].

Therefore, send not to know

for whom the bell tolls,

it tolls for thee.-John Donne, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Strikethroughs added.

Spark: Inspiration and background credit for this article belong to David Zilber, Alexa Firmenich, Joshua Kauffman, Merlin Sheldrake, Mt. Joy, The Analog Sea Review, Doug Rushkoff, Carl Safina, Lynn Margoulis, Steve Irwin, and others.

Thanks for this, Nate - super interesting.