Wild Animal Welfare

Do contraceptives for rats, airdropped chicken heads, and philosophy have something really important in common?

This post introduces the philanthropic cause of “wild animal welfare”, provides examples of its use in practice, and explores its purpose (Approx. 1,300 words, 5-10 minute read).

Wild Animal Welfare in Context

There is a fascinating new front opening at the intersection of animal rights, effective altruism, and nature conservation called "wild animal welfare”. It explores how humans might make life better for the trillions of wild animals we share a planet with.

Have you swerved to avoid a squirrel? Saved a baby bird? Adopted an old dog? Released a spider? Some sense of duty—altruistic, religious, biophilic, or otherwise—compels us to avoid unnecessarily harming animals and sometimes to help them.

Some people feel that duty especially strongly and become animal welfare (or animal rights) activists. Traditionally, those people focus on one or more of three areas:

Companion animals—pets like dogs, cats, parrots, and hamsters. Advocates seek to avoid abuse, neglect, and homelessness among these animals.

Farmed animals—food and textile providers like chickens, cows, pigs, and sheep. Advocates seek to improve conditions of living, handling, and slaughtering, and promote less animal product consumption.

Lab animals—research subjects like monkeys, rats, guinea pigs, and fish. Advocates seek to regulate inhumane and unnecessary experimentation, and to improve living conditions.

There are other “categories" of animals that humans directly interact with such as work animals (horses, etc), zoo/aquarium/park animals, and hunted/fished animals. There are no perfectly bright-lined categories: many species of animals are kept as pets, farmed for food, and used for experimentation or labor in difference places—like rats, dogs, rabbits, or horses.

Activists with a utilitarian view, like those in the Effective Altruism community, focus on farmed animals because the vast majority of domesticated animals are farmed animals living in factory farms: there are an estimated 40.5 billion farmed land animals and 125B farmed fishes (and >10 trillion insects), compared to 1.45B dogs/cats and 0.2B lab animals. Of the over 100 billion farm animals slaughtered annually, over 90% of those live in factory farms.

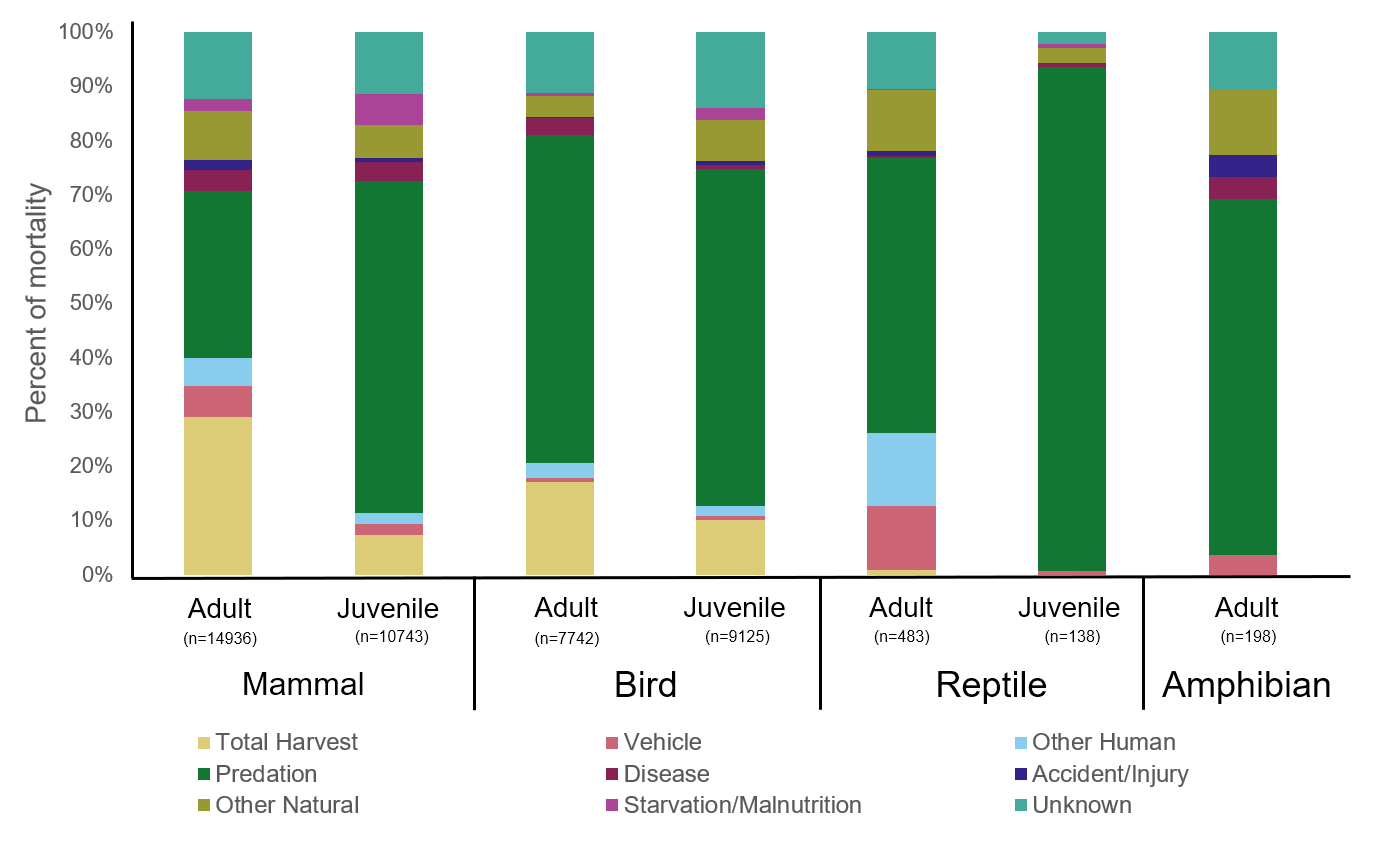

If we look at all animals, there are an estimated 10 trillion vertebrates and 10 sextillion invertebrates in the wild. These animals suffer in a variety of ways:

Natural

Predation, hunger, parasitism, and disease—these vary drastically by species but appear to be the main causes of wild animal death and certainly intense suffering

Human-caused

Agricultural and other pesticides—>1,000 trillion insects are killed by pesticides annually

Hunting, trapping, fishing, and culling—>1 trillion fish are caught annually, alone

Habitat destruction and pollution—agribusiness being the leading cause of both

Other/mixed: Natural disasters, climate change, invasive species, accidents (collisions, etc)

There is ample evidence that many animals, including numerous types of insects experience pain and display hallmarks of sentience. Therefore, there is an obvious impact-opportunity to reduce suffering by elevating the status of wild animal welfare.

Wild Animal Welfare in Practice

As a “field”, wild animal welfare is extremely new. I’m only aware of one dedicated nonprofit, the Wild Animal Initiative (WAI), founded in 2019. Wildlife conservation, of course, has a long history, and there is potentially considerable overlap in mission. I would argue that conservation charities should take up “compassionate conservation” as a sub-area, alongside biodiversity/habitat preservation, anti-poaching, and anti-pollution). Some conservationists elevate the teleological status of biodiversity from humanity’s “natural resource” to something of inherent value. That seems right, and it follows that we might care about the subjective wellbeing of sea turtles, whales, rhinos, etc. and not just whether the species is extant.

As a philanthropic field, wild animal welfare consists of the following three core activities:

Fundamental Research—interdisciplinary scientific groundwork for informed activism

How do we measure welfare (e.g. death/disease rates, behavioral/biological markers, mental capacity for suffering) and how do we capture that data? What constitutes a good life for a non-human animal?

What are the tools at our disposal, are they effective and safe?

Field Building—gathering resources to expand activism

How can we convince other activists to consider wild animal welfare?

How can we expand humanity’s “moral circle of concern” to include a greater range of creatures, beyond companion animals?

Welfare Interventions—implementing the research and resources in the real world

What are most effective uses of limited resources? Examples on this below

To make it more concrete, here is a short list of interventions that could be explored to improve wild animal welfare that fit into a few categories:

Reduce human-caused harm to wild animals

Environmental regulation—Pollution (chemicals and plastics) and habitat destruction probably the top anthropogenic causes of wild animal suffering. Absent a specific endangered species at risk, virtually no heed is paid to how wild animals are impacted by farm and factory pollution or property development.

New pesticides—A pesticide’s “mode of action” (MoA) is how it kills the target (and often non-target) animal, and they can be horrific. Attention could be paid to less painful MoAs, or non-lethal alternatives like birth-controlling chemicals or off-putting olfactory agents or acoustics.

Fishing and trapping regulation—Industrial trawling bycatch kills more than 600,000 highly intelligent dolphins and whales annually, and many orders of magnitude more of sea birds and fish. More than 6 million wild animals are killed by trapping in the US annually, often with inhumane steel jaw traps that are banned in the EU and elsewhere. Glue traps slowly kill an incalculable number of hundreds of animal species annually.

+/- Population control—Culling of invasive species, but also re-wilding of predators like wolves that limit starvation and disease deaths when carrying capacity is exceeded.

Others: more wildlife crossings, waste disposal improvements, meat replacements to offset agricultural demand.

Alignment between humans/domestic animals and wild animals

Parasite control—Since the 1960s, USDA has been sterilizing and shipping billions of flesh-eating New World Screwworms across the world in order to protect livestock herds. Wild animals are also benefitting from reduced Screwworm populations, and the same idea could be applied to many parasites that affect livestock, people, or pets, with the added benefit of helping offset R&D costs.

Animal vaccinations—Malaria is one of the worst diseases targeting humans. But, over 90% of Malaria strains target animals. This not only provides a breeding ground for new human-infecting strains that just the zoonotic barrier, but must cause tremendous suffering to animals. This is one of many examples, and has actually been done before by dropping rabies-vaccine-loaded chicken heads for foxes.

Other: Flood and fire control, habitat and climate conservation, animal language research.

Primarily philanthropic (economically or practically speculative)

Medical care—Euthanasia or treatment for injured animals; this is already done in the wildlife rescue space.

Birth control—Replacing lethal pesticides or traps with contraceptive ones, for example, instead of using cyanide in rat traps. We could also explore scalable contraceptive on animals that will likely die of starvation, especially when we know it will be a lean season.

Other: Feeding programs during droughts, genetic modifications, preventing/causing panspermia, application of stress-blocking chemicals during pesticide application or construction.

Ethical Considerations

Is it really the role of humans to intervene in the affairs of the “wild” or in “nature”? Might unintended consequences and human nearsightedness outweigh the good? If the state of nature is nasty, brutish, and short, does that mean that many wild animal lives are actually net negative from a utilitarian perspective, and can we change that? Otherwise, is a parking lot better than a forest? Can we ever compare the experience of a spider to a fly?

These are the tough questions that activists must grapple with as they chart new territory enabled by new technology, new information, and social progress. One thing is clear: human actions have an undeniable impact on the welfare of wild animals, as we do with Earth’s climate, farmed animals, lab animals, companion animals, and people on the other side of the world. We live in the Anthropocene. Like global poverty relief efforts, the field of wild animal welfare challenges us to think about whether suffering matters less if its far from our comfortable homes. There is always an opportunity for empathy, even if it might arouse strange sympathies.

For further reading, the Wild Animal Initiative’s Library is an excellent resource.

This is Fifth Industrial, a blog scouting emerging technologies and ideas for a regenerative economy and lifestyle. See the posts on the most impactful bioproducts, plant cell culture, cellular agriculture, mycelium materials, synthetic silk, microbiomics, deep space food, alt cheese, alt protein CPG, biophilia, agricultural innovation engines, longevity, egg sexing, and mosquito-borne disease.

A lot of great information here!